DISRUPTION 3.0: What’s Holding Networked Controls Back?

By Peter Brown

January 2, 2022

In this final article in our Disruption Series, we’ll look at network lighting controls (NLC) through the lens of the marketplace influences mentioned in the first two articles.

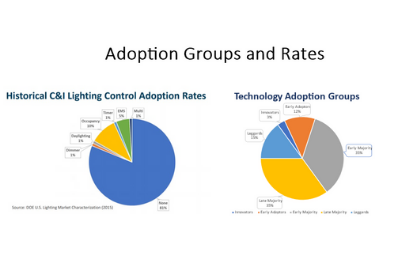

Prior to LEDs taking over the U.S. lighting industry, lighting controls comprised various non-networked products. Sensors were used for occupancy and daylighting, while timers were typically for exteriors. In a 2015 Department of Energy (DOE) report – U.S. Lighting Market Characterization – the commercial sector had 20% adoption of lighting controls. (See graphic at right)

When viewed alongside Geoffrey Moore’s Technology Adoption Lifecycle (as detailed in his book Crossing the Chasm), one sees that non-connected lighting controls have only penetrated a small part of the Early Majority group — even though these controls have been available for over 20 years.

With the digitalization of lighting to LEDs came digital control systems (i.e. multi-feature sensors, wireless/PoE, software, dashboards, mobile apps). A lot of those first-generation products were clunky, buggy, and complex. While this is to be expected, no one appeared to ask the most compelling question: Why, after 20+ years of availability, was only 20% of the commercial sector using non-connected controls? Consider it this way: If after 20 years, only 20% of T12s had been converted to T8s, one would expect questions as to why.

As Moore emphasizes in Crossing the Chasm – features and benefits only drive sales for Innovators and Early Adapters. Hence, the initial sale of a large project like Target stores (2016) was encouraging to the industry.

Why So Slow?

One large company created a group to sell advanced controls nationally, but after two years had disappointing results. Advanced controls were pitched with LEDs as a bundle. It looked impressive at first glance; however, as discussed in the second article in this Disruption Series, many commercial buyers look at financials first, with features and benefits a distant second. Therefore, they unbundled the solution and overwhelmingly bought just the LEDs.

While projects were initially spec’d with NLCs, invariably they were value-engineered out. Contractors became concerned that they would not get any work and began to show NLCs as an alternate. As lumens per watt continued to climb, the luminaire’s increased energy savings were in direct competition to NLC savings. The resulting diminished savings only increased the payback for NLC when looked at as a stand-alone ECM.

Another Hurdle

Further hindering mass adoption is the additional layer of cybersecurity concerns. Acuity Brands formed a Product Security Incident Response Team (PSIRT) in 2018 to supplement existing security programs by coordinating stakeholder interests regarding security concerns that potentially impact connected products and cloud-based infrastructure. All Acuity Brands products containing a software component, maintenance or management are serviced by PSIRT.

In an article by Liesel Whitney-Schulte and Dan Mellinger published in the November 2020 edition of LD+A Magazine, the state of network lighting controls was summarized as follows:

“Currently, fewer than 10% of new construction projects and 1% of lighting retrofit projects use networked lighting controls —this despite commercial incentives offered by more than 50 utilities across the U.S. and research showing that adding NLCs to commercial lighting projects can save an average of 47% more electricity than is possible with LEDs alone. Even with repeated promotion of NLCs as an energy-saving option through utility incentives and industry events and publications, barriers such as complexity, high initial cost, and lack of standardization and interoperability have largely trumped potential energy savings in the minds of designers and end users.”

Today, many in the controls industry and efficiency stakeholders still see the entire commercial market as having a single buying mindset. The assumption is that once the market has sufficient information and incentives, NLCs will follow a smooth adoption rate across all market segments.

As previously discussed, the Innovators are always the first buyers of the latest technology. The more disruptive the technology, the better. They live and breathe features and benefits. Unfortunately, they are only 3% of the market. The DOE’s latest estimate of connected lighting adoption was 0.2% in 2018, up from >0.1% in 2016. The best guess today is 1% to 2%, which means it is still in the Innovator stage.

A leading European NLC provider – Gooee – signed the largest NLC European project in 2019, but unfortunately, the customer cancelled months later. Gooee filed for bankruptcy in 2021.

What Does This Mean for NLCs?

These barriers are not a lack of education. They represent financial unknowns. The more unclear the financial implications, the greater the resistance. All the costs associated with complexity, lack of interoperability, and internal resource responsibility must be clearly defined. All costs have to be measurable so they can be monetized into a ROI calculation.

NLC, in its present form, is simply not ready to cross the chasm to mass adoption. Trying to promote, educate, and incentivize NLC does not change the value enough. Afterall, a free Segway still cannot handle stairs.

The solution requires a change of focus. Agendas of industry conferences since NLC inception have had very little representation by potential end-users. There is very little discussion on how C&I buyers determine value using ROI.

In September 2021, the DOE released the Connected Lighting Systems (CLS) Stakeholders Research Study, which does a great job of identifying the issues. For example, on page 27, in the Summary of Key Challenges, the study points out the “Consumer Lack of Perceived Value,” citing:

Many CLS stakeholders cited a lack of perceived value as the greatest barrier to adoption. Building owners generally do not see the need for advanced features and tend to want simpler, consistent, low-cost, minimum code level lighting systems. Tech-savvy building owners, tech companies, or businesses that create a unique user experience (museums, entertainment, hospitality, etc.) see more value in CLS. Also, the longer and uncertain payback periods of CLS present a challenge as energy savings can be highly variable.

The Bottom Line

One of the fundamentals taught to, and executed by, an MBA is to determine the ROI of every dollar spent. CEOs must exercise fiduciary oversight morally and ethically. This is why businesses unbundle lighting from lighting controls. When a reasonable improvement in cost and energy savings can be garnered through one technology but not another, the longer ROI is rejected (i.e. value-engineered out).

It’s not that a business doesn’t want CLS; it’s just that they are obligated to direct funds that provide the best return. There are always more funding requests than funds.

If this article appears to focus more on control financials than on control benefits, it’s intentional.

Not doing so is increasing evident in the widening gap between NLC forecasts and actuals. The possibility of legislating them in their present form will only lead to installation without optimization. This is the case with local lighting controls installed years ago that are still in place, but have been disconnected and/or overridden with manual-only usage, rather than be maintained or upgraded.

Either disrupt the current thinking toward NLCs, or their adoption will continue to be disrupted.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Peter Brown, LC, founded Lighting Transitions in 2018 as a Disruptive Technology Consultant who assists commercial companies in the U.S. transition from legacy lighting to a digitized, LED-based industry.

He is sharing his insight on embracing and profiting from disruption in the lighting industry through an exclusive three-part series for U.S. Lighting Trends.